By Ashley Waldron

All of the source code for this series can be found in this repository. Specifically, the code used throughout this item can be found here and its corresponding test classes found here.

Lenient mocking

Before version 2 of Mockito there was no such thing as ‘strict’ mocking. Everything was lenient and if you didn’t use the explicit mock verification methods in your asserts then there was a chance you wouldn’t find bugs in your code. Plus, strictness only became the default mode in version 2.3.

There was one nice advantage of lenient mocking though, and that was that you could have all of the default happy path setups in your @BeforeEach method. Each unit test then only needed to override whichever of those setups it needed to behave differently, in order to drive their respective scenarios. This cut down on the mock setup code in each method and in my experience made it easier to perform significant refactoring on a codebase. Because when a refactored class changes how it interacts with its external dependencies (or those dependencies themselves are refactored/redesigned) then most of the more awkward unit test refactoring is limited to the @BeforeEach method and small bits of each method.

But this was only true for disciplined unit tests which wasn’t always the case. What I’ve seen happen time and time again was that developers didn’t use the @BeforeEach method and simply copy and pasted large chunks of mock setup code from one test to the next (much of which wasn’t needed at all for the particular test) until they got the test working. With no strict mode in Mockito there was no problem doing this. Unfortunately, I’ve had the pleasure of performing sizeable refactoring on some of these code bases and when I did it was nothing short of a nightmare trying to figure out what mock setups were actually needed for each test and what way I needed to change them to get it working again. Often, I would just end up rewriting the test class from scratch because it was less insanity inducing!

The point of the above text is that using lenient mocking can be a valid approach to using mocking frameworks, but it needs to be used with extreme discipline. For that reason alone, I recommend strongly against it. Even though it took me a while to come around to the idea of the same mock setups being copied into many tests.

There is a caveat though which involves delving into the way Mockito works and finding out that the strict mock setups we’ve been using throughout this series don’t actually 100% double as verifications.

For example consider the following 2 versions of a unit test [Item10aUserServiceTest.createSuccessItem()]:

@BeforeEach

void setup() {

mockSavedUserEntity = TestDataCreator.createTestUserEntity();

createUserProfileRequest = TestDataCreator.createTestCreateUserProfileRequest();

}

@Test

void createSuccess() {

given(userRepository.save(userEntityArgumentCaptor.capture())).willReturn(mockSavedUserEntity);

given(employeeNumberGenerator.generate(TEST_REGION)).willReturn(TEST_EMPLOYEE_NUMBER);

CreateUserProfileResponse createUserProfileResponse = item5UserService.create(createUserProfileRequest);

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getEmployeeNumber(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMPLOYEE_NUMBER)));

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getEmailAddress(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMAIL_ADDRESS)));

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getRegion(), is(equalTo(TEST_REGION)));

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getId(), is(equalTo(TEST_UUID)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getEmployeeNumber(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMPLOYEE_NUMBER)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getEmailAddress(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMAIL_ADDRESS)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getRegion(), is(equalTo(TEST_REGION)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getId(), matchesPattern(UUID_PATTERN));

then(eventBroadcaster).should().broadcast(EventType.USER_REGISTRATION, mockSavedUserEntity);

then(emailService).should().registerSubscriber(mockSavedUserEntity);

}And [Item10bUserServiceTest.createSuccess()]:

@BeforeEach

void setup() {

mockSavedUserEntity = TestDataCreator.createTestUserEntity();

createUserProfileRequest = TestDataCreator.createTestCreateUserProfileRequest();

lenient().when(userRepository.save(userEntityArgumentCaptor.capture())).thenReturn(mockSavedUserEntity);

lenient().when(employeeNumberGenerator.generate(TEST_REGION)).thenReturn(TEST_EMPLOYEE_NUMBER);

}

@Test

void createSuccess() {

CreateUserProfileResponse createUserProfileResponse = item5UserService.create(createUserProfileRequest);

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getEmployeeNumber(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMPLOYEE_NUMBER)));

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getEmailAddress(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMAIL_ADDRESS)));

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getRegion(), is(equalTo(TEST_REGION)));

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getId(), is(equalTo(TEST_UUID)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getEmployeeNumber(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMPLOYEE_NUMBER)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getEmailAddress(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMAIL_ADDRESS)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getRegion(), is(equalTo(TEST_REGION)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getId(), matchesPattern(UUID_PATTERN));

then(employeeNumberGenerator).should().generate(TEST_REGION);

then(userRepository).should().save(any());

then(eventBroadcaster).should().broadcast(EventType.USER_REGISTRATION, mockSavedUserEntity);

then(emailService).should().registerSubscriber(mockSavedUserEntity);

}The first of these tests uses our usual strict mock setups and uses them to double as asserts. The second test is the same but uses lenient mock setups in conjunction with corresponding verifications in the assert part of the test. The 2 tests seem like they should be equivalent, but they’re not quite. We can see how they differ in their ability to warn us of when things go wrong by placing the following bug in the code [See Item10UserService]:

UserEntity userEntity = new UserEntity();

userEntity.setId(UUID.randomUUID().toString());

userEntity.setRegion(createUserProfileRequest.getRegion());

userEntity.setEmailAddress(createUserProfileRequest.getEmailAddress());

userEntity.setEmployeeNumber(employeeNumberGenerator.generate(createUserProfileRequest.getRegion()));

userEntity.setEmployeeNumber(employeeNumberGenerator.generate(createUserProfileRequest.getRegion())); //bug: calling employeeNumberGenerator.generate() twice

UserEntity createdUserEntity = userRepository.save(userEntity);We’ve made the code call employeeNumberGenerator.generate() twice by mistake. If we run the tests again, we see that the test which relies on strict stubbing to double as verifications still passes but the one which uses explicit verifications fails and exposes the bug in our code. The reason for this is because when you setup a mock (strict or lenient) you’re telling it “every time you get called with these parameters then do/return this”. So the setup doesn’t discriminate between different calls with the same parameters that may be made for it (unless you use the explicit consecutive call setups by chaining calls [.willReturn().willReturn().willReturn()], which generally only applies to a small number of specific test setups and isn’t the case for any of our tests). It’ll just keep returning what it was told to return no matter how many times it’s called. You can’t use them to tell you whether or not a mock was called more than once.

However, the verifications do check that a mock was only called the number of times that you intended. You’ll notice that the then/verify call has an overloaded method which takes the VerificationMode parameter. If you look at the Mockito source code, you can see that the default method actually just calls this with the value Mockito.times(1). So the following verification:

then(employeeNumberGenerator).should().generate(TEST_REGION);is equivalent to:

then(employeeNumberGenerator).should(times(1)).generate(TEST_REGION);This makes the mock verifications a more powerful way to assert that no funny business happened inside the method being tested. But there is a trade-off. In this example I had to grasp at straws a bit, the only mock call I could do this with was the one to employeeNumberGenerator.generate(). If you try to duplicate any of the other mock calls both tests will fail, and you’ll be able to eventually track down what caused the issue. There are 2 reasons for this:

- We never explicitly added a verification for

userRepository.save()in any of our tests. Most of us probably won’t think of doing this because we’re already using theuserEntityArgumentCaptorto verify that it was called with the correct values. If we already had thethen(userRepository).should().save(any());verification in our tests up until now, then both tests would have failed if we duplicated the call touserRepository.save()instead of duplicating the call toemployeeNumberGenerator.generate(). The way it is above both tests still pass because neither explicitly verifies that. - The rest of the calls to the mocked objects only call methods which return void. Which means that we already had explicit verifications in our tests for those calls (because we’re writing effective unit tests). Duplicating any of them instead causes both tests to fail. Note: This highlights the importance of always making sure to add explicit verifications to mocked method calls which return void. If you don’t add these verifications Mockito won’t warn you if it wasn’t called. Although the same is true for methods which return non-void objects, they’re more likely to blow up the test with a

NullPointerException(*see final note below). Alternatively, you can use thewillDoNothing()setup for mocking void methods and that doubles as a verification in the same way the other strict setups do. But I avoided doing that because I think verifications look a bit better and more explicit, andwillDoNothing()really only seems to exist to support chaining void method setups. Plus, as we can see in this item verifications are a bit more powerful. But you can choose to usewillDoNothing()instead of theshould()convention we’ve been using throughout these items. This would mean replacing the explicit verifications we’ve used so far with setups like this:

willDoNothing().given(eventBroadcaster).broadcast(EventType.USER_REGISTRATION,mockSavedUserEntity);Therefore, technically speaking it would be more powerful to not solely rely on strict mock setups for verifications and use explicit verifications for all mock calls in your tests.

But most of the time concerns like this are probably a bit overblown. It’s probably worth the trade off to just place your trust in the strict mock setups (for all non-void returning methods) because in most cases the above bug isn’t really a huge cause for concern. In saying that, there are 2 cases where I would definitely add the explicit verification to your unit test:

- When you’re calling an external method in a loop. You want to verify that call was made an exact number of times.

- When your code explicitly makes more than one call to the same method. Same reasoning as point 1.

Beware of the limitations of strict mocking

Sometimes when mocked methods return some (non-void) value it may be tempting to think that if we’re using lenient then we don’t need to add explicit verifications. Reasoning that if the correct parameters aren’t passed to the mock then it will return null and that will somehow cause things to go wrong. e.g. commonly this causes a NullPointerException to get thrown somewhere after the mock call when the code attempts to call methods on the returned object, which will blow up our test case. Allowing us to track it down and fix the issue. But this isn’t guaranteed. Sometimes your logic won’t call methods on the object after it’s returned. This means that just because a mock call returns an object it doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t add an explicit verification when using lenient(). Included in this note is the problem that mocked void returning methods can cause. Since the method doesn’t return anything there’s no need whatsoever to have any setup code for that method. When there’s no setup for the method then Mockito won’t tell you whether or not it was called at all. I’ve raised a request for enhancement with the Mockito project to make Mockito fail the test if a void returning method was called in strict mode but there was no setup or verification for it. But realistically I don’t see it going anywhere.

In summary, this item discusses that relying on strict stubbing to catch all potential problems interacting with external classes in your code has pitfalls, even though it’s a good practice. To protect against these pitfalls requires providing explicit verifications for everything on top of strict stubbing, which in reality would most likely be overkill. A good trade off would be to also provide explicit verifications for non-void mocked method calls if the code can actually call them more than once. Of course you should always have explicit verifications for void returning method calls, otherwise there’s no chance you’ll know if they’re being interacted with correctly. It may also be tempting to think that when we use lenient we might keep the testcase code smaller and more efficient overall, but this is only true when you write bad unit tests. When you use lenient to write good unit tests (with proper verifications) then it will probably come out more or less the same. The setup code is more streamlined but the assert code is larger. You can see that both Item10aUserServiceTest and Item10bUserServiceTest classes have the exact same number of lines overall.

Appendix

Keep an eye on the Mockito.shouldHaveNoMoreInteractions()/Mockito.verifyNoMoreInteractions() method. You’ll notice that we haven’t used this verification at all yet throughout the series. The reason for this is that there wasn’t really a strong need to. Our example code is fairly simple and doesn’t have anywhere that this verification is absolutely necessary. The reason I’m pointing this out though is to just be a little bit careful with how this verification works. Take the following unit test for example [See Item10aUserServiceTest.noMoreInteractionsA()]:

@Test

void noMoreInteractionsA() {

given(userRepository.save(userEntityArgumentCaptor.capture())).willReturn(mockSavedUserEntity);

given(employeeNumberGenerator.generate(TEST_REGION)).willReturn(TEST_EMPLOYEE_NUMBER);

CreateUserProfileResponse createUserProfileResponse = item10UserService.create(createUserProfileRequest);

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getEmployeeNumber(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMPLOYEE_NUMBER)));

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getEmailAddress(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMAIL_ADDRESS)));

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getRegion(), is(equalTo(TEST_REGION)));

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getId(), is(equalTo(TEST_UUID)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getEmployeeNumber(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMPLOYEE_NUMBER)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getEmailAddress(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMAIL_ADDRESS)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getRegion(), is(equalTo(TEST_REGION)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getId(), matchesPattern(UUID_PATTERN));

then(eventBroadcaster).should().broadcast(EventType.USER_REGISTRATION, mockSavedUserEntity);

then(emailService).should().registerSubscriber(mockSavedUserEntity);

then(employeeNumberGenerator).shouldHaveNoMoreInteractions();You can see at the bottom that we use the shouldHaveNoMoreInteractions() verification on the employeeNumberGenerator mock. If our brain is in the mode of thinking that since we’re using the strict mock setups as verifications, then if the employeeNumberGenerate.generate() method is called more than once, this verification should fail and bring the testcase down with it. But you’ll see that when you run this test it still passes (this is running against the same buggy code above which calls the employeeNumberGenerator.generate() method twice), much like our problem at the start of this item. Using shouldHaveNoMoreInteractions() won’t work for this verification. You’re stuck using the normal should()/verify() method (with the number of times if applicable) as shown in the previous section. You can even add in a verify which passes and the shouldHaveNoMoreInteractions() verification still won’t fail the test, e.g. [See Item10aUserServiceTest.noMoreInteractionsB()]:

@Test

void noMoreInteractionsB() {

given(userRepository.save(userEntityArgumentCaptor.capture())).willReturn(mockSavedUserEntity);

given(employeeNumberGenerator.generate(TEST_REGION)).willReturn(TEST_EMPLOYEE_NUMBER);

CreateUserProfileResponse createUserProfileResponse = item10UserService.create(createUserProfileRequest);

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getEmployeeNumber(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMPLOYEE_NUMBER)));

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getEmailAddress(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMAIL_ADDRESS)));

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getRegion(), is(equalTo(TEST_REGION)));

assertThat(createUserProfileResponse.getId(), is(equalTo(TEST_UUID)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getEmployeeNumber(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMPLOYEE_NUMBER)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getEmailAddress(), is(equalTo(TEST_EMAIL_ADDRESS)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getRegion(), is(equalTo(TEST_REGION)));

assertThat(userEntityArgumentCaptor.getValue().getId(), matchesPattern(UUID_PATTERN));

then(eventBroadcaster).should().broadcast(EventType.USER_REGISTRATION, mockSavedUserEntity);

then(emailService).should().registerSubscriber(mockSavedUserEntity);

then(employeeNumberGenerator).should(verificationData -> {}).generate(TEST_REGION);

then(employeeNumberGenerator).shouldHaveNoMoreInteractions();

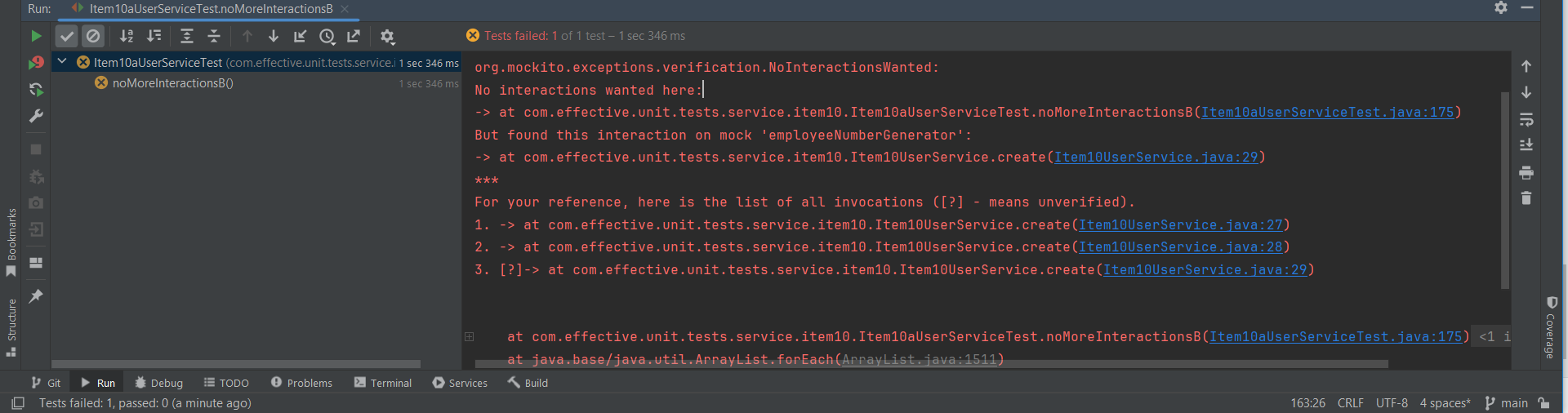

}e.g. Even though we’ve added a verification on line 174 (with a custom inline VerificationMode to bypass the times check). The shouldHaveNoMoreInteractions() on line 175 doesn’t flag anything and might give a false sense of security.

The shouldHaveNoMoreInteractions() method might have been called shouldHaveNoOtherDifferentInteractions() because it ignores methods that were setup (with particular parameters) and only throws a wobbler if some method on that mock was called without being setup (with those parameters). To see this in action just paste the following line after the 2nd call to employeeNumberGenerator.generate() on line 28:

employeeNumberGenerator.someOtherMethod();The test now fails with the following error:

Which is what we might have thought we’d get before we stuck in the call to the employeeNumberGenerator.someOtherMethod(). The problem here is that this verification does not flag if a method was called again with the same parameters.

To wrap this short section up, shouldNoMoreInteractions() mostly becomes helpful if the method you’re testing has calls to different methods on the same external class and you want to make sure that for certain scenarios those methods are not called. You could stick the shouldHaveNoMoreInteractions() call everywhere (even in our happy path tests) and it wouldn’t really be wrong, because you could say that you’re protecting against potential future introductions of calls to different methods (or calls to the same method with different parameters), but there are good reasons to consider that overkill. The official documentation for this method even says as much.

You’ll have to make a choice between how failsafe you want your tests be. You could use shouldHaveNoMoreInteractions() on every mock that doesn’t have the shouldHaveNoInteractions() for maximum piece of mind or you could restrict its use to methods and scenarios where the code does actually have multiple calls to the same external class and you want to verify that those calls are not made. I’ve used both approaches before but prefer limiting myself to the second. Whatever you decide just make sure that you’re aware of the quirkiness described above.